Definition "off-label use": When a medication is prescribed for a use or in a way that has not been approved, this activity is commonly referred as an “off-label use.”

The use for a medication is narrowly defined and includes the disease being treated, the dose, the duration of treatment, and the age group of patients for which the medication is intended. [1]

Introduction

In general, physicians are allowed to prescribe any available drug for any use - approved or unapproved. In the US, physicians don't even have to inform patients when prescribing a drug for an unapproved use. Though off-label use is pretty common (~20% of prescriptions), few patients are aware that they are receiving a drug off-label. However, in Germany the physician has to disclose all information and bears the liability risk. [1][2][3]

Why off-label use?

- Some physicians support off-label use, because they see it as “cutting-edge” medicine

- No approved drug available to treat a disease

- All approved treatments have been tried without seeing benefits

- New research shows that the drug may be effective for the given indication, but approval process is not finished yet

- Off-label prescribing by mistake due to drug's unclear approval status

- Economic rewards to manufacturers of off-label use sales can be enormous (though the promotion of prescription medications for off-label uses is not allowed)

Economic benefits to prescribers who accept cash and other gifts to prescribe medications off-label

- Cancer treatment: a chemotherapy drug approved for one type of cancer may actually target many different types of tumors

- The procedure of approvement is expensive

- Many drugs prescribed to children are used off-label because medications are less commonly tested in this age group [1][2][4]

Why not?

- Off-label prescribing can expose patients to risky and ineffective treatments

- Patients might not be aware of the risk

- Doctors carry the risk of lawsuits should a patient have unwanted or bad side effects [4]

- Pharma companies lose interest in doing clinical trials, not only because of the costs, but also since brand-name pharmaceuticals usually already have a big market-share regarding off-label use and so they would risk a potential negative outcome of a clinical trial [5]

Examples for beneficial off-label prescribing

Avastin (Bevacizumab) - There are only few drugs approved for the treatment of malignant brain tumors, Avastin (Bevacizumab) is one of them (was approved via accelerated approval). It is approved for recurrent glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) and some other (not brain) cancer types. But it is also prescribed "off-label" for newly diagnosed GBMs, as well as other brain tumors, such as astrocytomas due to the molecular similarities to GBM.

Avastin is a humanized monoclonal antibody and referred to as an anti-angiogenic drug. Angiogenesis is the process by which tumors are able to create their own blood vessels to feed themselves. Avastin targets a specific protein (VEGF) within the cancer cells that prevents the formation of new blood vessels. Hence it aims to kill a tumor by starving it of blood, which is the energy source it needs to grow. [6]

Beta-blockers - Beta-blockers are FDA-approved for the treatment of high blood pressure, but are widely recognized as standard care for patients with heart failure. Nowadays some beta-blockers are approved for treating heart failure, too. It's not unusual for off-label uses to get approved by the FDA someday.

Tricyclic antidepressants for chronic pain

Antipsychotics for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [2]

Examples for detrimental off-label prescribing

Fen-Phen - The medications fenfluramine hydrochloride and phentermine hydrochloride as individual are FDA-approved as short-term treatments for obesity. After an article in a medical journal and several mainstream publications described great weight loss effects, when taking a combination of “Fen” and “Phen”, physicians prescribed the two drugs together. As a result, many patients suffered from severe, and potentially deadly, heart valve damage. This triggered a multi-billion-dollar lawsuit and in 1997 Fen-Phen was withdrawn from the market.

Quetiapine (Seroquel) - Quetiapine is an antipsychotic drug and an example for doctors being confused about a drug's approval status: Some physicians thought it was also approved for dementia. But quite the contrary is the case: the medicine carries a "black box" warning (the FDA's sternest warning) stating that quetiapine was associated with an increased death risk in elderly patients with dementia. [2]

Gabapentin (Neurontin) - Gabapentin is FDA-approved for a certain type of seizure in children, which is not a large, lucrative market. So the management of the company started illegal, pharmaceutical marketing (it is forbidden to advertise off-label use), promoting 11 other uses for which gabapentin had not been shown to be safe or effective. The lawsuit was settled for $468 million, but this was just a small fraction of the billions of dollars of the company’s profits. [1]

Off-Label Use in Specific Sub-Groups

There are sub-groups for which clinical testing is not performed as often as for the general adult population and so they are exposed to off-label use considerably more than the general population. These groups include [7][9]

- Children

- The elderly

- Pregnant and nursing women

- Rare disease patients

The reasons for the lack of clinical trials vary with each group, but the general issue is the same - fear of risks presented to the tested population being too large to be socially acceptable.

Only with the rare disease patients the issue is not with the increased social sensitivity about these patients, but more a commercial calculus by the pharmacological producers, where developing medicine for rare diseases is highly unlikely to be commercially viable. Also, the low number of patients makes it difficult to get the required number of participants for a clinical trial.

Off-label use in children

The rate of off-label use in pediatrics is arguably higher than in any other fields[7][8]. This can be explained by several factors, which lead to research in children being more difficult than in adults.

These are [7]:

- The consent issues depending on the age

- Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic particularities in children

- Children are a more heterogeneous group than adults between 18 and 60 years - testing would have to be done for several sub-groups (e.g. 0-1 years, 1-3, etc.) [9]

- Different development speeds might make results for a statically given age-group irrelevant

- Possible parent's intervention

- Problems with specifying the proper dosage [9]

- Social pressures and ethical issues with testing on children

This often results in lack of research in this sub-group and in the drug monograph only mentioning age groups the drug was tested for (usually 18 years and above), while the drug may be very well safe for children. And since pediatricians may completely lack drugs that are tested for their target group and condition, they are forced to prescribe drugs not tested on children, against the manufacturer's recommendation and regulatory approval.

According to the Canadian Senate Report from 2014 [8], up to 75% of drugs prescribed to children in Canada are prescribed off-label.

In Europe, in cardiology and dermatology, only 19% of all medication prescribed to children is on-label, with percentages in other areas also being very high. [9]

Ways to decrease off-label use in children

This high prevalence of off-label use in children is an issue for regulators and clinicians alike. Off-label usage of drugs could be considered an uncontrolled experiment that does not capture information useful to understanding the drug’s effects and in which patients are unknowingly being enrolled. [10]

This lead to several initiatives aimed at either promoting clinical research in children or well as sharing data about medication used off-label to collect enough information to give clinicians a reliable statistic for continued use.[8][10]

As mentioned in [9], the UK and the Netherlands are dealing with the lack of medicines for children by means of a national formulary for children. These formularies provide practical information to clinicians on the use of medicines in pediatrics - indication, dosing, side effects, contra-indications and administration.

Both are regularly updated with the latest scientific evidence. This provides clinicians with much needed statistical data and improves their decision-making when using off-label drugs. It also makes health-care providers less hesitant about using off-label drugs, as the data compiled in the formularies is deemed reliable.

As mentioned in [7], the efforts to decrease off-label medication use in children are largely unsuccessful so far (or their impact won't be visible for several more years), as use of off-label drugs decreased only marginally in the last years.

Off-label use for pregnant or nursing women and the elderly

Pregnant and nursing women and the elderly are also a group for which most medication is not tested and their off-label prescription rates are very high.

As mentioned in [9], there are no comprehensive studies for the use of generic medicine for the elderly, but the use of medicine that has been tested on adults is non-strictly speaking off-label, unless there is an upper age limit or other restrictions for use in elderly patients mentioned in the drug monograph.

Also stated in [9], the rate of off-label use in pregnant women is 74% in the EU, which is again caused by the lack of clinical research done on pregnant women because of ethical reasons.

There is currently no policy in place in the EU to reduce off-label use in either pregnant women or elderly people. Only the usual post-marketing surveillance of medicines is performed in both these groups in the EU.

There are, however, some guidelines for using adult-tested medications in the elderly and also incentives to include elderly people in clinical trials in the EU [9]. Also, the European Medicine Agency has established the Geriatric Expert Group which deals with issues related to the elderly. This has caused more attention to gathering post marketing information in the elderly. Nevertheless, clinical trials frequently exclude elderly due to multi-morbidity[9].

Off-label use for rare-disease patients

Off-label use for rare diseases is widespread and caused by the lack of medication for rare diseases.

There are currently 7000 rare diseases, most of which are without a cure[11][12], additionally, the small number of patients per disease make it difficult to conduct clinical trials and also make developing such drugs unprofitable without government subsidies [9][12].

The high number of different rare diseases means that "Rare diseases are rare, but rare disease patients are numerous." [12]

Some statistics taken from [11]

- There are 7000 rare diseases with new ones being discovered rapidly

- In the US, a rare disease affects ~1 person out of 10

- It's estimated that worldwide, 350 million people suffer from a rare disease

- ~95% of rare diseases do not have a single FDA approved specific treatment [12]

- It's estimated rare diseases affect 6-8% of the EU population [13]

This leads to a great number of patients with need of treatment without any option other than off-label medication. According to [9], there is no comprehensive research done to summarize the prevalence of off-label medicine usage in rare-disease patients, but it can be expected to be very high.

Ways to decrease off-label use in rare disease patients

As mentioned in [12], there is a considerable number of rare and very rare diseases for which promising animal studies have been conducted. The financial and time investment required to continue with clinical trials outweighs the potential financial returns, so companies are not motivated to go through with them. This can be solved by either providing financial subsidies to companies developing cures for rare diseases, or allowing medicine for rare diseases to go through Accelerated Approval (AA) in the US and Conditional Marketing Authorization (CMA) in the EU, which lowers the requirements for clinical trial group sizes and softens other criteria. Drugs that pass AA or CMA are then observed in a clinical fashion after being administered to patients over a longer period of time and their efficacy and safety is evaluated.

In the US, the 1983 Orphan Drug Act is a collection of measures that aim at improving the pace of research for rare diseases. It has helped find cures for several hundred rare diseases (as of 2011 - 326 medications covering roughly 200 diseases [12]). It consists of incentives such as tax benefits, increased patent protection for cures and subsidies for clinical research. It also incorporated a government-run entity that engages in research and supports other researchers in a non-profit way - the Office for Rare Disease Research which started in 1993 and more recently, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences which was started in 2013.

In the EU, the efforts are more fragmented, spanning several programs that concentrate on rare disease research with different levels of participation by many countries. The methods are mostly identical as in the US act. [13]

Off-Label Responsibility and Reimbursement

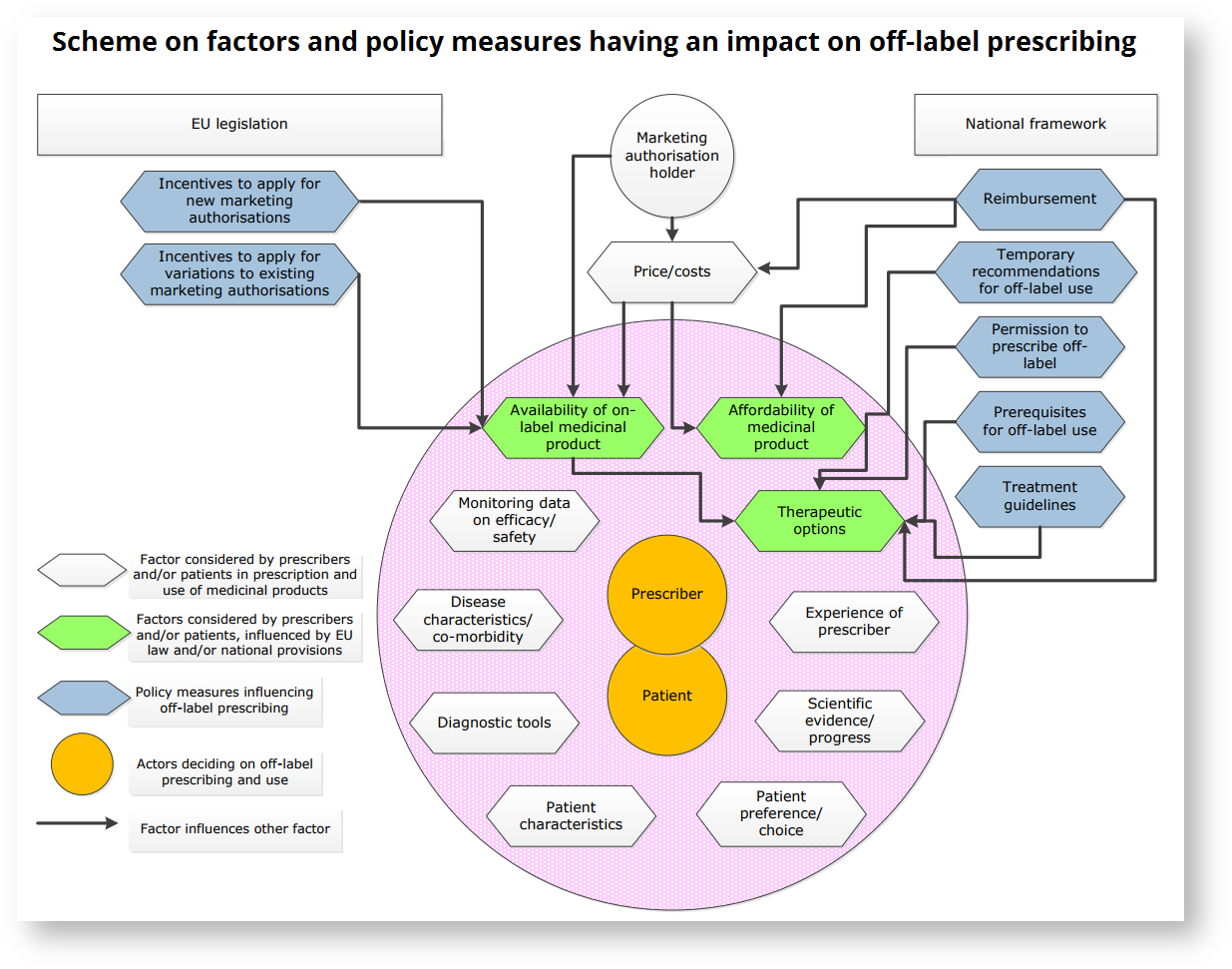

There are differences in the legislature governing the cases when the doctor is allowed to prescribe an off-label medicament and when the insurance company has to pay for the off-label prescription provided. A clear downside of off-label prescribing is that it puts all responsibility for the treatment on the prescriber, unless guidelines for off-label use of the specific medication are implemented in the country in question.

In the US and EU countries, a doctor is free to prescribe any medicine for any condition, as they best see fit. The doctor is free to ignore manufacturer's specification of indication, dosage, age requirements and so on. In doing so, they take responsibility of the treatment, as in the case of adverse effects, the manufacturer cannot be held liable if the drug monograph was not obeyed. [9][14]

In the EU, only France and Hungary have a comprehensive national legal framework for prescription of off-label medicine. The Hungarian system allows only for prescription of such off-label medicine with a risk-benefit analysis in place. The evaluation is based on population effects, so while possibly being advantageous to the whole population, it might be disadvantageous to individual patients. This might also be advantageous to the prescriber, as the personal responsibility is not as great.[9] France has a "Temporary Recommendation for Use" system in place, where off-label use is subject to monitoring and filling out a protocol about patients' reaction to treatment.

The reimbursement of the treatment in case of off-label use differs between EU countries. There are several approaches:

- only reimbursing off-label use in case of evidence (for example resulting in inclusion in treatment guidelines)

- only reimbursing off-label medicaments if they are a last resort to the patient, alternatives have been exhausted

- only reimbursing products for which there is no competitor in the market;

- allowing reimbursement of off-label use in case the off-label product is less expensive than its on-label competitor.

US legislation with relation to cancer treatment

In the US, the 1993 Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act mandated that Medicare provides coverage for off-label uses of drugs in anticancer chemotherapy if those uses were supported by designated compendia. The bill listed American Medical Association Drug Evaluations, American Hospital Formulary Service Drug Information (AHFS DI), and the United States Pharmacopeia Drug Information compendia, with the Secretary of the US Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) being given the freedom to update the list. The problem is that since that time, both of these compendia ceased to exist. [14]

In 2007, as there were no compendia from which the Secretary could take information to extend the list of treatments, the off-label list started becoming obsolete. This was solved by not explicitly naming the compendia in the legislation, instead giving a list of desirable characteristics a compendium should have and allowed the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) to add/remove suitable compendia to/from the list in a yearly review cycle. An important condition for the compendia is to provide a firm "Not Recommended" listing for an off-label treatment that was found to have serious side effects or not providing enough of a benefit. If a treatment is given "Not Recommended" by any of the compendia, then it is disqualified from being reimbursed even if other compendia consider it viable. [14]

Bibliography

1) What does “off-label use” mean?, https://www.express-scripts.com/art/pdf/kap54Medications.pdf (accessed 09/07/17)

2) Off-Label Drug Use: What You Need to Know, http://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/features/off-label-drug-use-what-you-need-to-know#1 (accessed 09/07/17)

3) Off-Label- Use, http://flexikon.doccheck.com/de/Off-Label-Use (accessed 09/07/17)

4) Understanding Unapproved Use of Approved Drugs "Off Label", https://www.fda.gov/forpatients/other/offlabel/default.htm (accessed 09/07/17)

5) Stafford R.S. (2008) Regulating off-label drug use-rethinking the role of the FDA, New England Journal of Medicine 358.14, 1427-1429

6) National Brain Tumor Society, http://blog.braintumor.org/files/public-docs/avastin-web-faqs-and-overview-final.pdf (accessed 09/07/17)

7) Unlicensed and Off-Label Drug Use in Children Before and After Pediatric Governmental Initiatives, Jennifer Corny et al. , Journal of Pediatric Pharmacology, 2015

8) Prescription Pharmaceuticals in Canada - Off-label use, Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology, Senate of Canada, 2014, https://sencanada.ca/content/sen/Committee/412/soci/rep/rep05jan14-e.pdf (accessed 11/07/17)

9) Study on off-label use of medicinal products in the European Union, Marjolein Weda et al., 2017, https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/files/documents/2017_02_28_final_study_report_on_off-label_use_.pdf (accessed 11/07/17)

10) A literature review on off-label drug use in children, Pandolfini, Bonati, European Journal of Pediatry, 2005

11) RARE Diseases: Facts and Statistics, https://globalgenes.org/rare-diseases-facts-statistics/ (accessed 11/07/17)

12) The potential investment impact of improved access to accelerated approval on the development of treatments for low prevalence rare diseases, Miamoto & Kakkis, Orphanet Journal of Rare diseases, 2011, https://ojrd.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1750-1172-6-49 (accessed 11/07/17)

13) European Commision - Policy on Rare Diseases, http://ec.europa.eu/health/rare_diseases/policy_en (accessed 11/07/17)

14) Recent Developments in Medicare Coverage of Off-Label Cancer Therapies, Journal of Oncological Practitioners. 2009 Jan; 5(1): p18–20.